Feeding and Equine Cushing's Disease/PPID

What's allowed? And what's not? Proper care and feeding of horses with PPID.

Equine Cushing's disease is the most common endocrine disorder found in older horses. What happens in the bodies of afflicted horses? Learn here how you can help your horse through adjustments to feed.

Do horses get Cushing's?

Although still commonly referred to as "equine Cushing's disease", the correct name for this condition is actually "pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction" (PPID). It is a disease of the pituitary gland (hypophysis) which produces symptoms that are similar to those experienced by people with Cushing's disease. This has extensive effects on hormone metabolism throughout the entire body.

The pituitary gland produces the important hormone ACTH and secretes it into the bloodstream. ACTH stimulates the adrenal glands to release cortisol. Cortisol is an endogenous stress hormone which affects the body's metabolism. The more ACTH circulating in the blood, the more cortisol the body releases. ACTH secretion is regulated by the transmitter dopamine. The body's ability to produce dopamine often decreases with age.

This, in turn, will affect the regulation of ACTH synthesis. Pituitary gland production of ACTH gets out of control, raising ACTH levels in the blood and causing the adrenal cortex to secrete more cortisol.

A disease with many different symptoms

Hormones carry out a variety of tasks in the body, which is why horses with PPID may experience a variety of symptoms. The most common sign noticed by horse owners is hair that is thick, long, and often curly (hypertrichosis/hirsutism) together with a difficult moulting in spring. Also typical for this disease are fat deposits over the entire body, most conspicuously in the hollows above the eyes, at the same time accompanied by increased muscle degeneration. Whilst horses are often still overweight in the disease's early stages, if it is left untreated, they will become emaciated as the disease progresses. Clearly recognisable signs of this development include lordosis (swayback) and a potbelly. Arguably the most consequential result of this hormonal imbalance, however, is laminitis, which affects more than half of all afflicted horses. Endocrine-related laminitis responds poorly to treatment, which is why it is essential that PPID be treated in time.

Other signs include:

- decreased performance, increased sweating

- increased water intake and urine output

- susceptibility to infection, chronic wounds

Diagnosis and treatment

The first suspicion of PPID is often due to the typical symptoms mentioned above. Even in horses that display all of these signs, blood tests to measure ACTH levels should always be carried out before beginning treatment as a control for later treatment success.

The veterinary surgeon will also consider seasonal fluctuations in ACTH levels when making a diagnosis, as even healthy horses will have increased ACTH levels in late summer and early fall. Important when taking blood samples: ACTH is unstable in blood, which is why the blood sample must be prepared and sent to the laboratory as quickly as possible. Otherwise it may lead to false results.

Although PPID is incurable, its symptoms can be treated; balanced management consisting of medication and feed adaptations can improve quality of life for many horses. Administration of pergolide can replace the missing dopamine to ensure regulation of ACTH secretion and, best case, return basal ACTH to normal levels.

Conventional PPID treatment can be complemented (but not replaced!) with chasteberry. Chasteberry's effectiveness is not yet fully researched but it appears to regulate the release of ACTH, similar to dopamine in the intermediate lobe of the pituitary gland.

Adapt feeding to individual requirements

At a glance: equine Cushing's disease

|

Many horses with PPID are prone to insulin resistance, meaning that they develop another metabolic disorder that facilitates the development of laminitis. It is therefore important to avoid feed sources that are high in easily digestible carbohydrates, for example starches and sugars. These stimulate insulin secretion due to blood sugar elevation and thus increase the risk of laminitis. Cereals in particular should be avoided, but also starchy feeds like rice bran. Alongside hay, the most suitable feeds are those that are low in carbohydrates and high in crude fibre but nevertheless provide enough energy to keep the horse in good condition. High-protein, high-fat feeds like lucerne, linseeds, and oils are ideal supplements, as horses with PPID are prone to muscle atrophy and emaciation.

Rations can be enhanced with compound feeds that contain high amounts of essential amino acids (such as lysine, methionine, and threonine) to support musculature. Amino acids are the smallest building blocks of proteins and help to build and maintain muscle. They are also involved in the formation and support of cell membranes and are important for metabolic processes.

A mineral feed configured for increased requirements should supply horses with PPID with all important micro-nutrients, including zinc, copper, selenium, and vitamin E.

Individual consideration of nutritional and health requirements and feeding that is adapted to individual needs can allow a horse to enjoy a long and healthy life despite a PPID diagnosis.

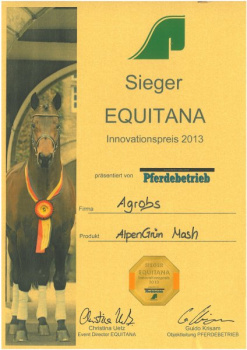

AGROBS feeds that can be fed to horses with PPID:

Daniela Hanke, B.Sc. Agriculture

June 2021, © AGROBS GmbH

June 2021, © AGROBS GmbH

Sources:

- Handbuch Pferdepraxis, Olof Dietz, Bernhard Huskamp, 4th edition

- Durham, A.E., McGowan, C.M., Fey, K., Tamzali, Y. and van der Kolk, J.H. (2014), Diagnosis and treatment of PPID. Equine Veterinary Education, 26: 216-223. doi:10.1111/eve.12160

- Seasonal Changes in ACTH Secretion, A.E. Durham, The Liphook Equine Hospital Laboratory, Liphook, GU30 7JG

- "Der Mönchspfeffer (Vitexagnus-castus L.), Behandlungsalternative beim Equinen Cushing Syndrom?", Nicola Schröer, Gabriele Alber, Zeitschrift für Ganzheitliche Tiermedizin, 4.2012